Pac-Man - The pleasure of the maze

When we think about Pac-Man, one of its indelible images involves the eponymous character running away from some colorful ghosts and later him being the one that chases them after getting a Power Pellet in order to eliminate them. Because of this, Pac-Man is usually cited as the first game with power-ups. However, the ghosts have a shorter duration of vulnerability after each level, and once you reach the twenty-first screen, those Power Pellets have no impact on them, and instead ghosts are faster, which represents how little actually mattered to director Toru Iwatani to entrance the player with the satisfaction of overcoming enemies they were previously weak to.

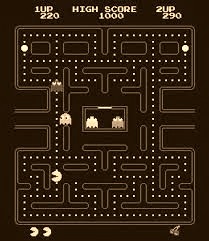

Pac-Man is a maze game where the player has to obtain all pellets and avoid ghosts that pursue the player to get to the next screen. Before its release, mazes in videogames were more closely associated with role-playing games such as Oubliette and Beneath Apple Manor, two great games of their generation that broadened the understanding of navigation in dungeons as social spaces or as a source of horror. However, the maze in Pac-Man is seen from a top-down perspective, while every element from role-playing games is absent. This is due to Iwatani's mechanical understanding of games, a consequence of his background as an engineer, and his interest in the development of pinball machines (which initially led to his first video game, Gee Bee, to have similar rules to pinball), where the immediate legibility of objectives is of paramount importance, and the abstraction of sensations is conveyed mechanically.

This element is precisely what differentiates Pac-Man from previous representations of a maze: Its economy in language, and its mechanization and legibility of simple components. If labyrinthis in role-playing games derive their strength from draining the player's resources, Pac-Man replaces this with the constant chase, where the game demands attention to avoid defeat and tests the mental fortitude of the player. By making the avatar move automatically in the direction it is facing, the implication of the player with the events on screen is bolstered, since not paying attention leads to not making decisions such as turning on bifurcations, or deciding between avoiding enemies and getting pellets on time. Through these resources, Iwatani blends the action derived from the chase and avoiding enemies on time with the labyrinthine construction of spaces in a way that seems natural, almost obvious and easy.

It is this feeling of ease that led Pac-Man to have numerous successors in its generation, but the fundamental difference between Pac-Man and other maze chase games is the depth in the movement speed. The avatar goes faster when it is not consuming pellets, can turn corners faster than the enemies, and can get through the lateral tunnels faster as well. Through this alongside the increasing speed of the enemies after each level leads to frequent situations where a player about to be caught escapes by very little from the enemies, in dodges at the last second, through which the player has to utilize the maze layout and search for appropriate places to gain more speed while being aware of their position in the screen. This element is Iwatani's true finding with Pac-Man: The pleasure of the maze, and this quality is what gives it true significance above superficial elements such as having the first mascot character or being the first game with cutscenes, and makes it, four decades and many sequels and variants after its release, still resonate with firmness.

Comments

Post a Comment